TL;DR

- Non-programmer built and shipped a 40-level Unity game in 2 months using Claude Code

- “Vibe coding” means describing game feel (snappy, crunchy, floaty) instead of writing code

- PostToolUse hooks automated build-test cycles, feeding errors back to Claude for instant fixes

- Best for: hobbyist game developers who understand feel but lack coding skills

- Key lesson: Describe sensations, not syntax; AI translates vibes into variables

A hobbyist with zero C# experience shipped a polished platformer in two months by describing game feel to Claude Code instead of learning to program.

Dylan had never written a line of C# in his life.

He’d played games for twenty years. He had strong opinions about what made games feel good. Jump timing. Camera weight. The satisfying thunk of a hit landing.

But implementing those feelings in code? That required skills he didn’t have.

“I knew exactly what I wanted. A precise platformer with crunchy jumps and responsive controls. I just couldn’t build it.”

Then he discovered “vibe coding” — and built his first game in two months.

The Concept

Vibe coding meant describing game feel instead of writing code.

“I’d tell Claude: ‘The jump feels floaty. Make it snappier with more initial velocity and faster fall.’ Claude would adjust the physics parameters.”

Dylan didn’t need to understand the math. He needed to describe the sensation. Claude translated vibes into variables.

“It’s like working with an infinitely patient technical collaborator who speaks your language.”

The Setup

Dylan used Unity — the game engine he’d seen recommended for beginners. He installed Claude Code. Then he created a feedback loop using hooks.

The PostToolUse Hook: Whenever Claude modified a C# file, a hook automatically triggered a Unity build.

The Feedback Loop: If the build failed, error messages fed back to Claude. Claude fixed the issue. The build tried again. Repeat until success.

“I’d describe what I wanted. Claude would code it. The hook would build it. If it broke, Claude would fix it. All I did was describe and test.”

Day One: Movement

Dylan started with the most fundamental thing: making a character move.

“I want a character that can run left and right. Movement should feel responsive — no acceleration lag. Stop immediately when I release the button.”

Claude generated a movement script. The hook built it. Dylan tested in the Unity editor.

“The character moved. First try. I’d expected to struggle for days on basic movement. It took twenty minutes.”

He refined: “The run speed feels slow. Increase it by maybe 30%. And add a little visual tilt when changing direction.”

Claude adjusted. The hook rebuilt. Dylan tested. Better.

The Jump

Getting jump to feel right took longer.

“Every platformer lives or dies on jump feel. I had strong opinions here.”

Dylan’s description: “Jump should have high initial velocity — really launch the player. Then gravity increases after the apex so falling feels faster than rising. Variable jump height based on button hold duration. And a little coyote time — let me jump for a few frames after leaving a ledge.”

Claude implemented. Dylan tested. Too floaty. More adjustment. Too snappy now. Back and forth.

“We went through maybe fifteen iterations on jump alone. Each one took minutes because the hook automated the build-test cycle.”

The final jump felt… right. That ineffable quality of a well-tuned platformer.

The Feedback Hook Detail

The hook that made this possible:

hooks:

post_tool_use:

- pattern: "*.cs"

command: "unity-headless-build.sh"

feedback: trueWhen Claude saved a C# file, the script ran a headless Unity build. Success or failure output fed back to Claude’s context.

“Build failed: CS1002 - ; expected at line 47”

Claude would immediately see the error and fix it. Dylan never had to context-switch to the Unity editor to check compiler errors.

“The hook transformed development from ‘write-compile-error-switch-fix’ into ‘describe-wait-test’. Entirely different experience.”

Week Two: Combat

Dylan wanted a simple combat system. Describe, don’t code.

“When I press attack, the character should do a quick slash animation. If an enemy is in range, damage them. I want hit pause — the game freezes for a frame on impact for crunch. And a screenshake. Small, subtle, but it should feel like the hit landed.”

Claude implemented: attack input, hitbox detection, damage dealing, frame freeze, camera shake.

“I tested it and felt the impact immediately. That satisfying micro-pause when sword meets enemy. Claude understood ‘crunch’ as a concept.”

The Iteration Speed

Dylan tracked his development velocity.

Traditional learning curve: understand C#, understand Unity APIs, write code, debug errors. Estimated time for a first game: 6+ months.

Vibe coding curve: describe what you want, test what you get, describe refinements. Actual time: 2 months.

“I’m not saying I learned to code. I didn’t. I’m saying I built a game. The goal was the game, not the education.”

The Art Problem

Code wasn’t the only blocker.

Dylan couldn’t draw. His programmer art looked terrible. But Claude could help here too.

“Describe the visual style I should use for a dark fantasy platformer. What assets should I look for? What color palette?”

Claude suggested aesthetic directions. Dylan browsed asset stores with guidance. The game looked coherent — not because Dylan had art skills, but because he had good taste and a translator.

Month Two: Polish

The core game worked. Now came polish.

“Add dust particles when the character lands from a jump. Trail effect on the sword swing. Subtle parallax on the background layers.”

Each request: describe, implement, test, refine.

“Polish is usually where hobbyist games die. You’ve built the mechanics, but the game lacks juice. With Claude, adding juice was as easy as asking for it.”

The Learning That Happened Anyway

Dylan noticed something unexpected: he was learning.

“I didn’t study C#. But after two months of seeing Claude’s code and asking ‘why did you do that?’, I started understanding patterns.”

The Unity API became familiar. Not through tutorials — through seeing it used to implement his ideas.

“I couldn’t write the code myself. But I could read it and understand it. That’s a different kind of learning.”

The Published Game

The game shipped on itch.io.

40 levels. Boss fights. Responsive controls. That “crunchy” feel Dylan had envisioned.

Player feedback: “Tight controls.” “Feels good to move.” “Who made this?”

Dylan’s answer: “I made it. With a lot of help.”

“I didn’t misrepresent anything. The game design was mine. The feel was mine. The code was a collaboration. That’s legitimate authorship.”

The Philosophy of Vibe Coding

Dylan thought about what the experience meant.

“Games are about feel. The code is implementation detail. Why should feeling-people be locked out of making games because they’re not code-people?”

He wasn’t claiming to be a programmer. He was claiming to be a game designer who used AI to implement designs.

“Writers don’t need to understand printing presses. Filmmakers don’t need to understand camera sensors. Game designers shouldn’t need to understand compiler theory.”

The Limitations

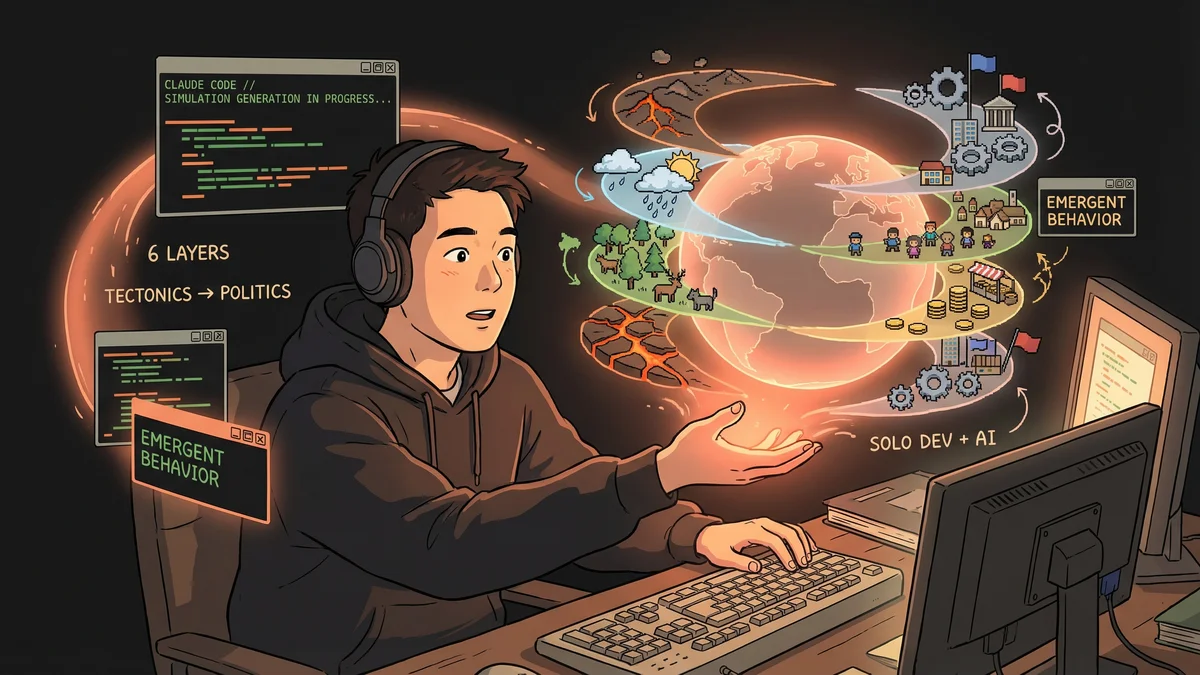

Not everything worked via vibes.

“Networking code for multiplayer? Too complex for description. AI behavior with emergent properties? Couldn’t describe it precisely enough.”

Simple games with clear feel requirements worked best. Complex systems needed actual engineering understanding.

“Vibe coding works for games about feel. It struggles with games about systems.”

The Current Project

Dylan’s second game is more ambitious.

A metroidvania with progression systems. He’s learning more actual code this time — the vibes only get you so far with interconnected systems.

“Claude helped me get started. Now I’m pushing into territory where I need to understand more. The curiosity came from seeing what’s possible, not from studying prerequisites.”

The Recommendation

For aspiring game developers intimidated by code:

“Just describe what you want. See what happens. The build might fail. Claude will fix it. Iterate until it feels right.”

The technical barrier to game development used to be: can you code?

Now it’s: can you describe what you want and recognize when you get it?

“That’s a much more accessible bar. Lots of people have game feel intuition. Now they can act on it.”